From the DailyClout.io

Understanding C-19 Vaccine Efficacy Clinical Trial in Lay Terms

The Moderna vaccine decreases the production of antibodies to the nucleocapsid in a dose dependent fashion in those who acquire COVID after vaccination.

Four months after injection, 40% of vaccinated participants who acquired COVID after the second injection produced antibodies to the nucleocapsid, compared to 93% of those who received placebo injections.

In participants that were COVID positive on the day of Dose 1 injections (before the vaccinations had time to work) a robust production of anti-nucleocapsid antibodies occurred in both placebo and vaccinated groups, with no difference between the groups. In the participants that acquired COVID between doses, a reduction in anti-nucleocapsid antibodies was observed in those who received the vaccine compared to those who received placebo. The reduction was not as severe as the group who acquired COVID after the second dose. Thus it appears the more doses received, the more severe the reduction in anti-nucleocapsid antibody production.

Moderna vaccination in people that have never had COVID previously reduces the production of anti-nucleocapsid antibodies compared to placebo. This may reduce the strength and duration of immunity to COVID compared to unvaccinated immune responses. The more doses, the less the production of anti-nucleocapsid antibodies.

Further investigation is warranted with all COVID vaccine types in larger populations, to determine if this phenomenon is observed in all COVID vaccine products, because they all use the spike protein mRNA. This would include Pfizer/BioNTech, Jannsen, Astra-Zeneca and Novavax. Also, it is important to determine the relative effectiveness of the anti-nucleocapsid antibodies versus the anti-spike antibodies against COVID and its variants.

If the mRNA vaccines decrease the production of anti-nucleocapsid antibodies in a dose dependent fashion, immunity would be short-lived and possibly lessened with additional boosters, the opposite of the desired outcome. This decreased immunity would affect all vaccinated people who had no COVID previous to their vaccination.

A nested sub study was performed on participants that got COVID during the blinded phase in Moderna’s Phase 3 clinical trial for themRNA-1273COVID vaccine. The purpose of this nested study was to determine if vaccinated people produce or maintain the anti-N ab at the same level as those who are not vaccinated after getting COVID. The sub study was discussed inmedRxiv, “Anti-nucleocapsid antibodies following SARS-CoV-2 infection in the blinded phase of the mRNA-1273 Covid-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial” byFollmann, D., Janes, H.E., et al.

This study compared the production of antibodies (from the viral nucleocapsid) in participants that received placebo to those who received the vaccine.

A nucleocapsid is a protein that envelops the viral genetic material for its protection.

In contrast, the spike proteins protrude out from the nucleocapsid and are responsible for the virus being able to enter human cells to cause COVID.

The antibodies against this nucleocapsid are abbreviated as “anti-N Ab.”

The antibodies to the spike protein are abbreviated as “anti-S Ab.”

For simplicity, this summary will just use the term “vaccine” when discussing the Moderna mRNA-1273 COVID vaccine. SARS-CoV-2 is the name of the virus that causes COVID.

The blinded phase of a clinical trial is the portion in which the participants did not know if they received placebo or vaccine.

Briefly, the blinded portion of the Phase 3 clinical trial design consisted of two groups: those receiving two doses of placebo, and those receiving two doses of the vaccine, 28 days apart. Treatments were given on Day 1 and Day 29, and participants were followed for approximately four months, at which time they were told which treatment they received and the trial was, thus, unblinded. This time point was called the “Participant Decision Visit” or “PDV.” The nested portion includedCOVID tests taken from all participants on Day 1, Day 29, and during any symptom-prompted illness visits to diagnose COVID infection. Serum samples from Days 1, 29, 57, and the PDV were tested for anti-N Ab levels by immunoassay.

The Results

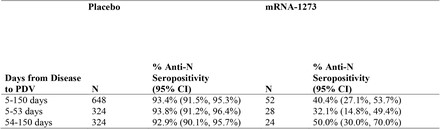

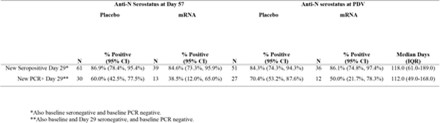

Table 1 shows positive anti-N ab tests at the PDV for participants with COVID detected at an illness visit during the study. These participants had no previous COVID illness prior to the study so therefore acquired it during the study. A substantial difference in anti-N ab production was shown between groups: 40.4 percent (21/52) in vaccine recipient COVID cases versus 93.3 percent (605/648) in placebo-recipient COVID cases. Thirty-six of the 52 vaccine recipients also had anti-S ab levels measured. Twenty of them were anti-N ab negative, and 16 of them were anti-N ab positive. Among these 36 individuals, the anti-S ab titers were not significantly different between those who were anti-N ab negative or those who were anti-N ab positive. This indicates that the vaccine did not negatively impact the level of the anti-S ab as it did with the anti-N Ab. Not surprising, considering that the vaccine causes the body to produce the spike protein only, without a nucleocapsid. It makes sense that vaccinated individuals would have robust anti-S ab production due to large amounts of the spike protein present.

Table 1

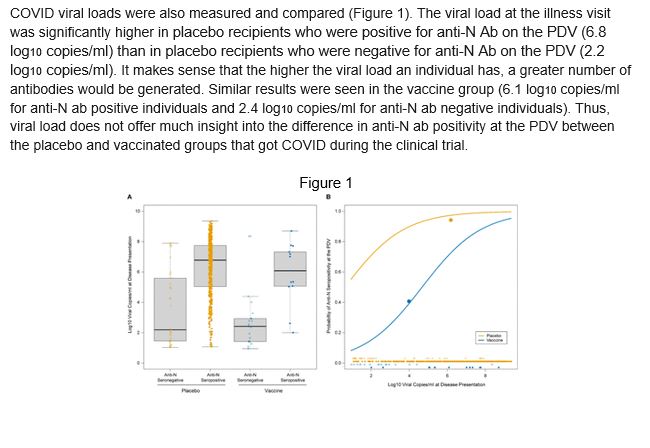

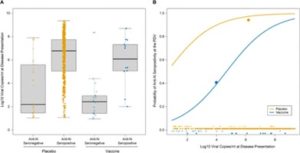

COVID viral loads were also measured and compared (Figure 1). The viral load at the illness visit was significantly higher inplacebo recipients who were positive for anti-N Ab on the PDV (6.8 log10copies/ml) than in placebo recipients who were negative for anti-N Ab on the PDV (2.2 log10copies/ml).It makes sense that the higher the viral load an individual has, a greater number of antibodies would be generated. Similar results were seen in the vaccine group (6.1 log10copies/ml for anti-N ab positive individuals and 2.4 log10copies/ml for anti-N ab negative individuals). Thus, the viral load does not offer much insight into the difference in anti-N ab positivity at the PDV between the placebo and vaccinated groups that got COVID during the clinical trial.

Figure 1

These data show that, among the participants with PCR-confirmed COVID, anti-N Ab positivity about 53 days post diagnosis occurred in 40% of the vaccine recipients vs. 93% of the placebo recipients. Though it is possible the vaccine caused a loss of anti-N ab, given the short time frame it is more likely that the vaccine reduced the production of the anti-N ab.

A comparison was made of ‘anti-N ab levels per viral load’ in study participants that were ill on Day 1 to the ‘average anti-N ab level per viral load’ over all illness visits. This comparison showed the virus reproducing at Day 1 illness more than at other time points in the study, meaning that at Day 1 (before the vaccinations had time to work) more anti-N ab was produced in response to the magnitude of the viral load.

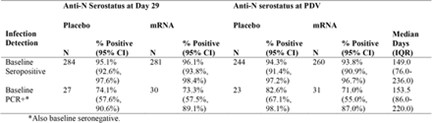

Comparison of placebo versus vaccinated recipients with COVID detected at baseline showed similar anti-N ab production rates at both Day 29 and PDV for both groups (Table 2). These robust ab titers were also maintained through the PDV for both groups, which indicates that actual infection before vaccination created robust anti-N ab titers that were long-lasting.

Table 2

Comparison of participants from both groups that became ill at Day 29 and were anti-N ab positive, showed no difference between placebo and vaccinated groups at day 57 and at PDV. For those participants that were anti-N ab negative but had a positive PCR test for COVID on Day 29, the positivity rates are 60.0 percent (18/30) for the placebo group and 38.5 percent (5/13) for the vaccinated group at Day 57 and 70.4 percent (19/27) and 50.0 percent (6/12), respectively at the PDV. Consistent with the effects seen among baseline infections, the Day 57 and PDV anti-N ab positivity rates are significantly lower for Day 29 PCR-positive. Anti-N ab-negative participants were also compared to Day 29 anti-N ab-positive participants in both groups, but the vaccinated group was significantly lower than the placebo group.This indicates that even one vaccine on board seems to depress the anti-N antibody production, though not as severely, suggesting that the more vaccinations taken the greater the reduction in anti-N ab production.

Table 3

This data shows that, among the participants with COVID, anti-N Ab production occurred in 40 percent of the vaccine recipients versus 93 percent of the placebo recipients. While an increase in the loss of these antibodies cannot be ruled out, given the short time frame, the more likely explanation is a vaccine-induced reduction in production of them. Anti-N ab production correlated with viral load, with each log increase in viral load nearly doubling the odds of anti-N ab production at the PDV. These lower anti-N ab titers in the vaccine recipients could be partly explained by their reduced exposure to the nucleocapsid antigen and/or overwhelming spike protein exposure. Alternatively, it could be explained by a combination of these. There may be other features of the initial course of infection that influence anti-N Ab production and are affected by vaccination. The average viral load across post-COVID illness visits did not correlate or influence anti-N ab titers at PDV.

The authors of the original article were more concerned with determining a population’s prevalence and incidence of past COVID infections while using the anti-N ab titer. However, this author thinks the main takeaway is that vaccination with the Moderna vaccine actually reduces the production of anti-N ab compared to placebo and, thus, may reduce the strength and duration of immunity toward COVID compared to unvaccinated immune responses. This phenomenon increases with the number of vaccinations received. The sub study authors believe that the anti-S abs alone provide enough immune protection, which in the short-term may be true since 648 placebo recipients fell ill during the study compared to 52 vaccine recipients. This was a very short time period that was studied, only four months. Natural immunity after getting a disease often protects for a lifetime.

Statistics do not support long-lasting immunity for the COVID vaccines since many more vaccinated people are getting COVID than unvaccinated (Mercola, J., May 25, 2022, “Is this the worst excuse for vaccine failure yet?,” Z3News). This remains true even with people receiving up to three or four vaccinations. Another paper published online discusses this as well (Eur J Epidemiol. 2021; 36(12): 1237–1240. “Increases in COVID-19 are unrelated to levels of vaccination across 68 countries and 2947 counties in the United States.” Subramanian, SV and Kumar, A. Published online 2021 Sep 30).

Finally, this article from National Library of Medicine shows the higher the vaccination rate in a country, the higher the number of COVID cases; and countries with lower vaccination rates have lower numbers of COVID cases.

In conclusion, the immunity provided by the vaccines is short-lived, and it could partially be explained by the lack of anti-N ab production after vaccination.

This Report was written exclusively for DailyClout by the Members of the War Room / DailyClout Pfizer Documents Research Volunteers.

It should not be copied or republished without permission from DailyClout or a full credit and link to DailyClout.io