Normally, by September, the drive north from Sacramento on Interstate 5 showcases vast stretches of flooded rice fields on both sides, farms bustling with tractors and workers preparing for fall harvest.

Not this year, said Kurt Richter, a third-generation rice farmer in Colusa, the rice capital of California where the local economy relies heavily on agriculture. “It is now just a wasteland,” he said.

As drought endures for a third year with record-breaking temperatures and diminishing water supplies, more than half of California’s rice fields are estimated to be left barren without harvest — about 300,000 out of the 550,000 or so in reported acres, provisional data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows. This year, rice is estimated to account for just 2% of total planted acres across the state.

The Sacramento River Valley is among the top producers of rice, an important staple, in the United States, second only to the Grand Prairie in Arkansas. Rice crops contribute more than $5 billion a year and tens of thousands of jobs to California’s economy, according to the California Rice Commission. Much of the sushi rice consumed in the U.S. is grown there.

The dramatic reduction in rice acreage will translate to lost revenue of an estimated $500 million, about 40% of which will be covered by federal crop insurance, according to UC Davis agricultural economist Aaron Smith.

But one side of the valley is faring decidedly better than the other.

West of the Sacramento River, in Colusa County, many rice fields look “abandoned,” Richter said, with sprawling patches of dirt clods with dryland weeds growing atop, which signal trouble not only for the farmers and their workers, but the migratory birds that travel to and feed in those fields. Any moisture has been sucked dry by this year’s scorching heat, he added.

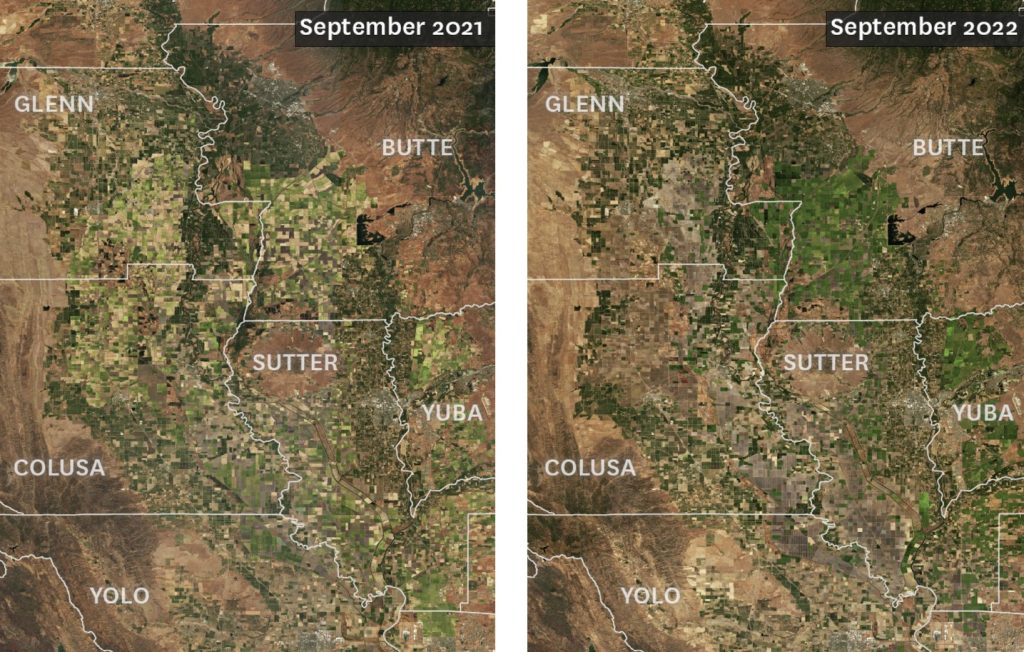

Meanwhile, in Butte County, lush green fields can still be seen from space, as shown in the imagery above from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel satellite. Butte County farmers actually planted slightly more acres of rice than last year.

“The difference is the source of water,” said Luis Espino, a farm advisor at UC ANR’s cooperative extension in Butte. Eastside farmers depend on Lake Oroville, which was able to capture more water than Shasta Lake, where the current storage is less than half of the average storage for this time of year.

The farmers in the Sacramento River watershed who rely on water from Shasta, including Richter’s family farm operation, are receiving somewhere between 0 and 18% of their water deliveries this year from government-run water projects. Farmers in Butte and Yuba counties received far more — about 75%.

Among the six top rice-producing counties in the Sacramento River Valley, four are expected to plant significantly less than last year. Only Butte and Yuba remain relatively unscathed by the scorching drought.

The picture looks most grim for Colusa, a county of about 21,000 people, where the data shows some 120,000 acres of rice land is estimated to remain unplanted.

The impacts of drought have been devastating and far-reaching, Richter of Colusa said. “It’s been as ugly as we anticipated it could be,” he said. Of the 5,000 or so acres in his family’s farm operation, where he is the vice president, just 1,300 acres have been planted this year. The rest remain barren.

The Richter farms have been able to keep their full-time staff, but won’t be hiring any seasonable labor this year, nor any subcontractors, the farmer said. “We just don’t have anything for them to do.”

“Rice will likely rebound again once this drought ends, but this year’s massive reduction feels like a harbinger of tough times ahead for California rice,” Smith, the UC Davis agricultural economist wrote in his August analysis.

But when will the drought end? Will there be enough water?

These questions remain unanswered, with each passing day of drought inducing more anxiety about the days ahead, Richter said.

“There’s a dark, metaphorical cloud hanging over our heads that we’re going to have another short or non-winter,” Richter said. “It’s weighing heavily on everyone’s minds,” he added.

Crop insurance won’t last forever, he said. There are limits to how much can be claimed. His family is considering planting non-rice winter crops to make up for some of the loss, as well as conducting research trials to figure out how to grow rice with less water.

If this drought continues for another year, Richter worries there won’t be any water left for anyone. “When there’s no water to haggle over, then what? I don’t think anyone knows,” he said.

Espino, the Butte-based farm advisor, said the options are limited for rice farmers in the Sacramento River Valley, and continued drought would likely result in only those with the economic capacity to withstand the financial swings brought forth by the drought remaining.

But it’s hard to predict what exactly will happen this winter — if there will be plentiful rain to nourish these lands once more. “Nobody really knows what’s going to happen,” he said. “The only thing we can do is keep positive and hope/ pray for rain.” [SF Chronicle]