On June 26, the CDC issued a health advisory when Texas and Florida reported cases of malaria. The five diagnoses — one in Texas and four in Florida — quickly made headlines, with CDC officials reporting that these are the first cases of malaria to originate inside the U.S. since 2003. The CDC notes that while the US was once a malaria-endemic country, the disease was eliminated here in 1951.

The persons in Florida resides in Sarasota County while the person in Texas, an outdoor worker, resides in Cameron County. Even though approximately 2,000 cases of severe malaria are diagnosed each year in the US, most are acquired from travel to malaria-endemic countries. Diagnosing five cases of malaria from within the US is considered a “medical emergency” by the CDC, recommending that “anyone with symptoms should be urgently evaluated.”

All people have been treated and have recovered.

The CDC has deemed this an “unusual spread” and is calling for states to issue public health alerts. Naturally, the CDC offers the following advice:

- avoid being outside during the “high mosquito” times of the day

- spray your body with (toxic) mosquito repellants, such as EPA registered repellents

- spray your clothing with the toxin, permethrin and

- use window screens and mosquito netting when sleeping.

Malaria is a serious and potentially fatal disease caused by transmission of a parasite through the bite of an Anopheles mosquito. Any of the five known species of this parasite in the genus Plasmodium can cause the illness: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi.

More than 240 million people around the world become ill each year from malaria and about 625,000 (mainly children) die from the disease. Symptoms start 10 to 30 days after the mosquito bite, and include flu-like symptoms of fever, shaking chills, sweats, headache, body aches, nausea, and vomiting. Left untreated, malaria can be life-threatening and can cause disorientation, seizures and other neurological symptoms. It can also result in low red blood cell counts (anemia), acute respiratory distress syndrome, and kidney damage (from hemolytic anemia). Laboratory abnormalities can include anemia, thrombocytopenia (low platelets), elevated bilirubin, and elevated liver enzymes. The infection can range from mild and uncomplicated to very severe and even death.

Treatments that have been historically used for prevention and treatment of malaria have been quinine, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. Quinine, obtained from the bark of cinchona trees, was first discovered in the 1600s and was used as a major therapy for malaria until the 1920s.

1934: Chloroquine (CQ) was first synthesized as an anti-malarial drug but was not widely adopted for medical use due to its toxicity.

1940s: CQ was re-synthesized then tested for safety and efficacy. By introducing a hydroxyl group to CQ, hydroxychloroquine was found to be a less toxic metabolite. HCG was introduced into clinical trials in 1946.

1955: HCQ was finally approved for use along with CQ for malaria prevention and treatment.

While taking HCQ for malaria prophylaxis, many patients reported an improvement in autoimmune-induced rashes, inflammatory arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Soon, an off-label use was approved for HCQ (trade name Plaquenil) and for many decades, it has been commonly used to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

At least since 2003, it has been well established that both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine could disrupt the replication of several families of viruses, including flaviviruses, retroviruses, and coronaviruses. Multiple articles reported that the drugs could be used both prophylactically and therapeutically against coronavirus infections. The resistance to using HCQ to protect healthcare workers and others from contracting covid 19, saying there was no proof of efficacy or safety, was unfounded. Between 2013 and 2020, more than 486 million prescriptions of HCQ had been written in the US alone. Safety had been solidly established for a medication that has been used for decades.

CQ and HCQ were the first-line treatments for malaria for decades due to low-cost and very few side effects. However, the extensive use of these drugs over the last 20 years has resulted in the emergence of drug resistant P. falciparum strains.

Most treatment protocols for malaria include one of 5 extracts of artemisinin (ar-tem’-ess-in-in). The artemisinins include artesumate, arteeter, artemether, artemisinin, and dihydroartemisinin. The compounds are derivatives of the Chinese herb known as “qing hao” or the sweet wormwood plant (Artemisia annua). Artemisinin-derived drugs are used worldwide and are always given in combination with other antimalarial drugs to prevent resistance.

In the 1970s, Professor You-You Tu was the head of an antimalarial research group and is credited with discovering artemisinin, a Chinese herbal extract. You can read the fascinating path to its discovery here.

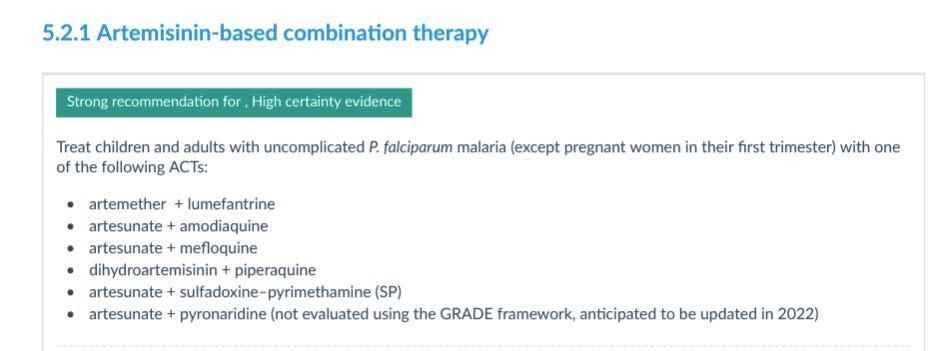

In 2005, the WHO announced a change in strategy to treat malaria by advocating artemisinin combination therapy (ACT). Artemisinin derivatives rapidly clear the parasites from the blood, leading to a speedy resolution of symptoms, but as then it is quickly cleared from the system. Used in combination with a slower acting antimalarial drug, the remaining parasites can be eliminated over three days of treatment.

ACT is now used to across Africa to save many lives and to reduce both the intensity and the duration of symptoms. On June 3, 2022, the WHO released a new, 396 page GUIDELINES for treating malaria. Section 5.2.1 Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapy (pg. 142) begin a very long section on the recommended drugs, protocols, and dosages of malaria-based pharmaceuticals.

Some of the following medications have potentially serious side effects.

- Coartem – (long list of warnings and drug interactions) The most common option for uncomplicated malaria is a combination of artemether and lumefantrine. Artemether has a rapid onset of action and is thought to provide faster symptom relief by reducing the number of malaria parasites in circulation. Lumefantrine has a much longer half life and is believed to clear residual parasites. The exact mechanism by which lumefantrine exerts is unknown.

- Camoquin – This is a combination of artesunate and amodiaquine. As far back as 1951 this medication was used as a single dose treatment for resolution of malarial symptoms. The drug was relaunched in Africa by Sanofi-Aventis in 2007 under the name ASAQ. It has a reduced-dose treatment with few side effects: Adults take 2 tablets per day for three days and infants and children take one tablet a day for three days.

- Mefloquine – This anti-malarial medicine was sold under the trade name, Lariam. At one time, it was widely distributed to people in the US military being deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan and Africa. It is no longer used because it caused serious neurological side effects, including hallucinations, confusion, anxiety, PTSD, and suicidal thoughts.

- Malarone – This is a combination of atovaquone-proguanil. The drugs in this combination are interesting: atovaquone, generally used to treat pneumocystis carinii, the type of pneumonia most likely seen in persons with HIV and proguanil, an antimalarial drug used to block the parasite’s reproduction process. It is only available in the US as a prescription for persons traveling to countries where malaria is prevalent

- IV Artesunate – In May 2020, the FDA approved IV artesunate. There has been no FDA-approved drug in the US available for treating severe since quinine was discontinued by the manufacturer in March 2019. Look at the potential adverse reactions associated with this medication:

The most common adverse reactions reported (2% or greater) include acute renal failure requiring dialysis, hemoglobinuria (blood in urine), and jaundice. Anemia severe enough to require transfusion can occur up to 4 weeks after treatment; this may be evidence of hemolytic anemia.

The CDC is advising hospitals to have a plan for rapidly diagnosing and treating malaria within 24 hours of presentation. Isn’t it just convenient that now this drug is approved for use in the US, we have 5 cases of endemic malaria show up?

And only 5 cases have been diagnosed. Hmm. More “fear porn”?

Beyond the convenience of having “just-in-time” treatment available for malaria’s big come back in the US, are there possible reasons for the outbreaks on Southern border?

CBS News described the Texas malaria case as “a person who works outside.” As it turns out, that person is 21-year-old Christopher Shingler, a National Guard member stationed near the Texas-Mexico border. Sometime in May, Shingler experienced vomiting, fever and eating difficulty. When he tested negative for Covid-19, he was told he probably had a different viral infection. When Shingler’s symptoms persisted into June, he sought help elsewhere and malaria was confirmed from a drop of his blood. Shingler has not traveled recently, so could he have acquired the disease from one of the illegal immigrants coming across our southern border?

This is not out of the realm of possibility. Malaria spreads when a mosquito becomes infected with the parasite after biting an infected person, and the infected mosquito then bites a non-infected person.

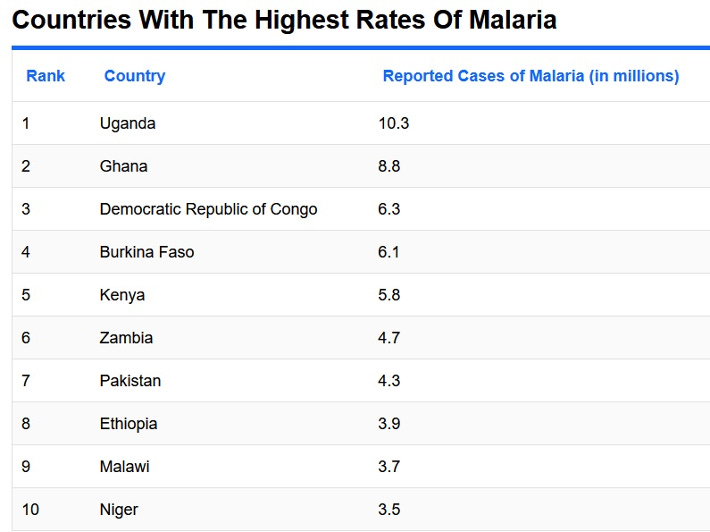

Almost all cases of malaria in the US are from other countries with ongoing malaria transmission. According to the WHO, CDC and others, most of the countries that have malaria are in Africa.

Thousands of people from African nations have been surging across the border since 2019. The Mexican government corroborates that data, saying their country has seen a sizeable increase in immigrants from African nations.

Table courtesy of World Atlas.

On a recent trip to the US-Mexico border, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said 600 to 800 people crossed into the US illegally on the night he was there. Kennedy described the situation as a dystopian nightmare: “No country can survive if it can’t control its borders,” Kennedy said.

In November 2021, Biden restricted travel from African nations reporting the omicron variant. Soon afterward, Texas Governor Greg Abbott began to receive reports of African people illegally crossing the border, and, of course, there is no ban on the massive illegal crossings happening every day.

What other diseases might be walking into our country?

It’s worth mentioning that the largest Level 4 Biolab in the world is quite close to Cameron County. The Galveston National Laboratory (GNL) on Galveston Island is less than 200 miles away by car, a straight shot down the coastline. GNL specializes in diseases that “are of grave concern to the NIH”— and malaria is on that list.

GNL not only looks at the disease-causing parasites but it is also investigating mosquitoes as the disease vectors. Furthermore, their website states that malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases are a high priority for study, given their “potential to be used as weapons around the world.”

We wrote about GNL in The Tenpenny Report late last year. You’d think that the GNL would comment on the outbreaks, but as of July 1, they’ve said nothing. Peter Hotez commented on the malaria case, saying that the Gulf Coast has areas of persistent poverty and is therefore the epicenter for mosquito-borne viral infections.

ZME Science wrote the following about the malaria reports:

The new cases are a reminder of the possibility of malaria becoming more common in the US because of global warming. Higher temperatures allow mosquitoes to live longer and grow faster. While before they would likely die in winter in many places, now they have a better chance of surviving and expanding their global populations.

A warming world has favorable effects on the mosquito population, allowing mosquito larvae to mature faster and causing mosquitoes to bite and feed on humans more frequently.

Tackling the growing greenhouse gas emissions is the most direct approach to avoid temperature increase and a further spread of malaria. But as the world is not acting fast enough, it will be important to be prepared.

It should not go unnoticed that Florida and Texas are the two states where Bill Gates’ genetically modified marauder mosquitoes have been released.

In July 2009, Gates gave a TED talk about malaria, where he said that he considered the mosquito to be the most deadly animal in the world, and that he was going to do something about it. He talked about genetic engineering and actually released (normal, uninfected) mosquitoes into the audience.

Nearly a decade ago, I wrote an article about DNA modification of mosquitoes in The Tenpenny Report (previously Vaxxter.com) Scientists who were investigating ways to eliminate malaria incidentally discovered how to modify the DNA of mosquitoes to stop malaria spread.

In fact, Bill Gates funds the World Mosquito Program (← watch that video) which breeds 30 million mosquitoes per week in a Medellin, Colombia laboratory and releases them in 11 countries in an attempt to eradicate dengue fever.

The World Mosquito Program introduced the Wolbachia bacteria into male mosquitoes to block the capacity of the insect to spread parasites. Wolbachia is a form of bacteria which naturally infects some insects. Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes are being used as a tool to control mosquito populations. Infected males can be released into an uninfected population. When they mate, the females will not produce any progeny, thought to eventually result in a population decline.

In addition to funding the World Mosquito Program, Gates also funds the British biotech firm Oxitec.

The Gates Foundation Global Grand Challenge indirectly awarded Oxitec $5 million in 2005. A larger $20 million anti-malaria project by Oxitec seems to have received Gates’ funding for its Aedes mosquito work. The firm was awarded another $4.1 million in 2018.

Oxitec is developing a different way to modify mosquitos: They insert a limiting gene into male mosquitoes. When these GMO males mate with the normal females that are responsible for the disease transmission, the inserted gene prevents the offspring from surviving beyond the larval stage. Over time, in theory, there will be a decline in disease-carrying insects.

In 2021, Oxitec released male Aedes mosquitoes in the Florida Keys to combat Dengue fever and stop the spread of the Zika virus. The CDC reported only a very small number of dengue cases in Florida that year and no confirmed Zika cases in the entire US since 2019, so why release the GMO mosquitoes n 2021? Many Florida residents were not happy when they found out about the release; they felt they had been subjected to experimental form of targeted pest control.Ma

Hawaii is not thrilled at having biopesticide-carrying, experimental mosquitoes released across its islands. Tina Lia, the founder of Hawaii Unites, an environmental nonprofit group, has filed a temporary restraining order against the State of Hawaii to stop the mosquito release in East Maui. The state already released the Wolbachia males in mid-May, despite a pending lawsuit. Lia and tropical disease expert Dr. Lorrin Pang were recent guests on Dr. Tenpenny’s Brighteon.TV show, On Your Health, every Monday at 7:00pEST

Dr. Pang noted that new life forms coming to the islands have the potential for “unexpected, dangerous, irreversible evolutionary consequences, particularly when new organisms can’t be contained to their target ecosystems.”

Pang also spoke about studies showing that Wolbachia can cause mosquitoes to become more capable of spreading other diseases like West Nile virus, instead of inhibiting the spread, as the “experts” claim. The details of the release have been kept secret from the Maui community, and this release of mosquitoes is the largest ever, nearly 90 times larger than any global release to date.

“Hawaii is not a petri dish for corporate experiments,” Lia said.

In 2021, the same year as the inaugural mosquito release in Florida, the WHO supported widespread use of a new (experimental) malaria vaccine for sub-Saharan African children. The recommendation is based on results from an ongoing pilot program in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi that had already vaccinated more than 900,000 children since 2019. Prior to the start of the new initiative, more than 2.3 million doses of the vaccine have been administered in 3 African countries. WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Ghebreyesus touted it as a “historic moment.” And of course, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided catalytic funding for the development of vaccine between 2001 and 2015.

In 2022, the NIH funded clinical trials to determine whether mosquitoes could “vaccinate” humans. Each human participant was paid $4,100 to dip their arm into a chamber of hungry GMO mosquitos that could deliver live malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites to their bloodstream. The GMO-modified parasites were not supposed to make people sick and the lead investigator, Dr. Sean Murphy exclaimed, “We used the mosquitoes like they’re 1,000 small flying syringes”. Dr. Kirsten Lyke, who led the phase I trials for Pfizer’s Covid-19 jab and was a co-investigator for both Moderna and Novavax, calls the NIH research “a total game changer.”

Indeed.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. sums it up best in a recent tweet: He doubts Gates’ intentions are purely noble:

“Should Bill Gates be releasing 30 million genetically modified mosquitoes into the wild?”

What could possibly go wrong?

Source: Malaria in the News – by Dr. Sherri Tenpenny