For all the talk about a potential recession, the Biden administration doesn’t seem to care much about damaging the economy. Witness the latest attempt to impose “equity” that will only raise costs, while hurting the housing market in the process.

Beginning today, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which governs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, is changing the fees those enterprises charge on new mortgages. FHFA claims the changes will “more accurately align pricing with the expected financial performance and risks of the underlying loans.”

Nice try. What the changes will really do is reduce fees for people with lower incomes and lower down payments. In other words, people with higher credit risks paid for by higher fees on lower-risk borrowers. Or, as Barack Obama more colloquially put it, FHFA is “spreading the wealth around.”

Encouraging Risky Behavior

FHFA arose from the taxpayer-funded bailout of Fannie and Freddie during the 2008 financial crisis. The changes the agency is imposing this week are part of a larger review of the guarantee fees the entities charge, purportedly to ensure they reflect the risk of default on behalf of the borrower.

FHFA recently published a blog post attempting to defend the changes. In doing so, it attacked what it dubbed “misconceptions” about the proposal, including this one: “Higher-credit-score borrowers are not being charged more so that lower-credit-score borrowers can pay less. The updated fees, as was true of the prior fees, generally increase as credit scores decrease for any given level of down payment.”

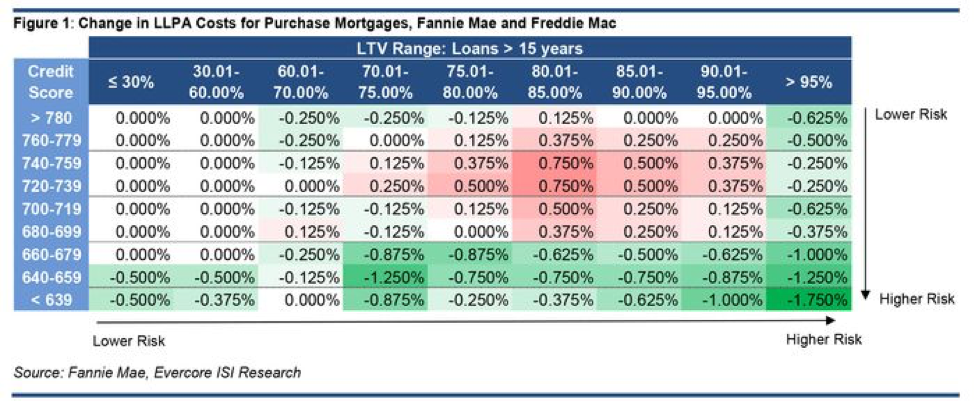

That sounds nice in theory until one examines a chart published by Evercore ISI Research showing the specific impact of the changes:

As the chart illustrates, only borrowers with credit scores above 680 — that is, those with good credit, and at lower risk of default — are paying more for their mortgages. By contrast, borrowers with lower credit scores are paying less.

Similarly, while borrowers putting down less than 5 percent on their mortgage are having their fees reduced, no matter their credit score, borrowers who put down 15, 20, or even 30 percent will often see their fees increased. (Borrowers who put down less than 20 percent generally have to pay private mortgage insurance, or PMI, to cover the risk of default; these FHFA guarantee fees are separate and distinct from PMI premiums.) This is “risk-based pricing” how exactly?

The facts, specifically real-world housing experience, show it isn’t. A recent Wall Street Journal editorial cited American Enterprise Institute data on mortgages taken out just before the financial crash:

Among borrowers with credit scores between 720 and 769 and 20 percent down payments, the default rate was between 4.2 and 8.8 percent. Among borrowers with less than 4 percent down payment and credit scores between 620 and 639, the default rate was between 39.3 and 56.2 percent.

Broadly speaking, then, the people who will pay less in fees have default risks roughly 5-15 times higher than the people who will pay more.

Opaque Subsidies

FHFA tried to defend some of these changes by claiming that “the targeted eliminations of up-front fees for borrowers with lower incomes … primarily are supported by the higher fees on products such as second homes and cash-out refinances,” and that Fannie and Freddie have a mandate that “include[s] references to supporting low- and moderate-income families.”

But the problems with this mentality are several. First, the Federal Housing Administration already provides low-cost loans to borrowers with limited credit histories and/or small down payments. The FHFA changes cannibalize from existing government programs and overcharge people with good credit in the process.

Second, to the extent that the changes move away from risk-based pricing, and the facts above strongly suggest they do, they introduce distortionary effects into the housing market. Borrowers with good credit might become dissuaded from buying a house by the prospect of paying fees they should not have to.

Conversely, borrowers with poor credit or small down payments may become incentivized to borrow more house than they can afford. While interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve have currently slowed the housing market, at some point the FHFA changes could exacerbate house price increases, as introducing new borrowers into the market would bid up the price of the housing stock. And if some lower-credit borrowers run into financial difficulty, this trend could result in the kinds of problems (i.e., defaults and foreclosures) that plagued so many communities during and after the financial crash.

The FHFA changes come with generally laudable goals, namely expanding access to home ownership. But as in so many other programs advanced by the left, the old axiom about the road to perdition being paved with good intentions applies.

**Source: ‘Low-Risk’ Borrowers Will Pay Higher Mortgage Fees For ‘Equity’