Wearing a face mask results in exposure to dangerous concentrations of carbon dioxide in inhaled air, even when the mask is worn for just five minutes when sitting still, a study has found.

With surgical masks, the CO2 concentration of inhaled air exceeded the danger zone of 5,000 ppm in 40% of cases. With FFP2 respirators it exceeded it in 99% of cases. The CO2 concentrations were higher for children and for those who breathed more frequently.

The study, a pre-print (not yet peer-reviewed) from a team in Italy, used a technique called capnography to take the measurements of CO2 in inhaled air over the course of five minutes, following a ten minute period of rest, with participants seated, silent and breathing only through the nose. A medic took measurements at minutes three, four and five, with an average of the three measurements being used in the analysis.

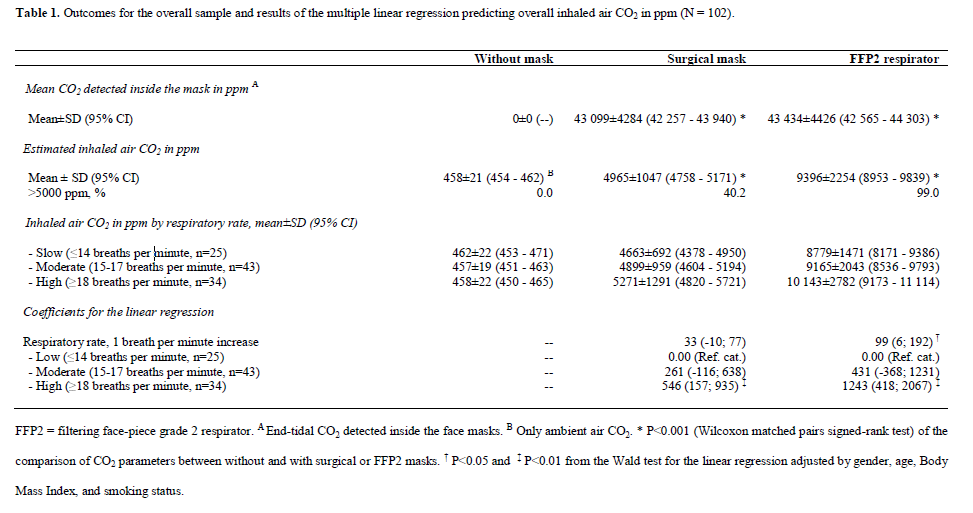

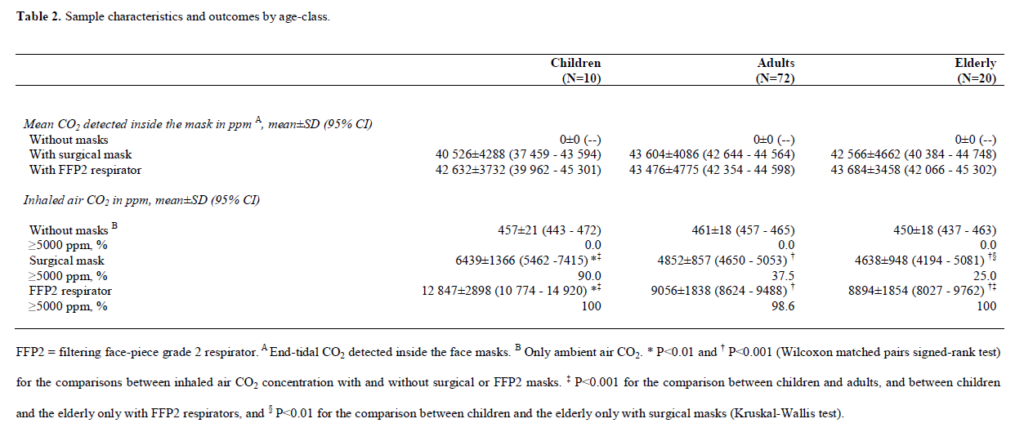

The study found the mean CO2 concentration of inhaled air without masks was 458 ppm. While wearing a surgical mask, the mean CO2 was over 10 times higher at 4,965 ppm, exceeding 5,000 ppm in 40.2% of the measurements. While wearing an FFP2 respirator, the average CO2 was nearly double again at 9,396 ppm, with 99.0% of participants showing values higher than 5,000 ppm. Among children under 18, the mean CO2 concentration while wearing a surgical mask was well above the safe limit at 6,439 ppm; for an FFP2 respirator it was nearly double again at 12,847 ppm. The researchers found that breaths per minute only had to increase by three, to 18, for the mean concentration to reach 5,271 ppm in a surgical mask and breach the safe limit.

While the findings are clearly concerning enough, the researchers note that “the experimental conditions, with participants at complete rest and in a constantly ventilated room, were far from those experienced by workers and students during a typical day, normally spent in rooms shared with other people or doing some degree of physical activity”. In such conditions the CO2 concentration of inhaled air is likely to be considerably higher.

While the study did not find a reduction in blood oxygen saturation during the five minutes of observation of a person at rest, the authors note that research on 53 surgeons wearing masks for an extended period found that blood oxygen saturation decreased noticeably. They add that exposure to CO2 in inhaled air at concentrations exceeding 5,000 ppm for long periods is “considered unacceptable for the workers, and is forbidden in several countries, because it frequently causes signs and symptoms such as headache, nausea, drowsiness, rhinitis and reduced cognitive performance”.

The authors note this is the first study to assess properly the CO2 concentration of inhaled air while wearing a face mask. Two earlier studies were small and did not adequately remove water vapour. A third recent one was retracted for, among other concerns, not using a capnograph to distinguish inhaled and exhaled air. The present study addresses these problems. The full results are shown in the tables below.

The study is a pilot study, and so calls for larger and more detailed studies to confirm the effects it observes and explore them further. The authors remark that should their findings be confirmed (and there is no reason to expect they would not be), mask-wearing should be “reduced as much as possible when the [Covid] risk is low”.

We might add that, given the lack of evidence masks do much if anything to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and the mounting evidence they do harm, they should be jettisoned as a pandemic measure entirely.