As financial markets and media remain focused on recession timing and debate over when the Federal Reserve will flip to cutting interest rates, growing threats to the U.S. food supply—exacerbated by government policy—go under-appreciated.

Concerns of a global food shortage have been mounting given the war in Ukraine and the huge amounts of fertilizer, wheat, and other food-related exports that come from that region.

Many economists and strategists say a food shortage can’t happen here. After all, the U.S. produces most of its own food and roughly half of domestic land is used for agricultural production, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

There are several overlapping reasons, however, why America shouldn’t take a sufficient food supply for granted.

Eva Slatter, a farrier in Emory, Texas, travels from farm to farm to take care of horses’ hoofs and has a small farm of her own. Her neighbor is selling his herd of cows, and a local livestock auction earlier this month brought out more trailers than she had ever seen, with ranchers looking to sell backed up for miles.

Record temperatures and the worst drought in more than a decade mean there isn’t grass for the animals to eat, and hay—the alternative—is tough to come by as higher fuel costs make it harder to transport from other states. The cost of hay in her area is around $220 a roll, compared with about $45 in normal times and $120 in a typical drought year, she says.

“None of the ranchers I know want to get out, but they have to,” Slatter says of the livestock liquidation. “Everybody is selling because they can’t feed them, and no one is buying the cows to raise.” That suggests more meat and lower prices in the near term. But the Texas Farm Bureau said in a report this past week that with much of the current breeding herd going to processing plants, calf numbers will fall in years ahead. As Slatter puts it, if everyone sells out of cattle now, what are we going to do later on?

About 250 miles away from Slatter, Stephen Brantley is getting nervous—but for a different reason. Brantley, a longtime banker at Waggoner National Bank in Vernon, Texas, says his bank has been fielding calls lately from farmers approached by solar companies interested in their land. First the companies ask to test the land over about a year, during which time the farmer can continue growing crops such as wheat. Then, if the testing goes well, the solar company either offers to buy the land or lease it for 20 to 30 years.

The offers are hard to refuse. Farmland often best meets solar-site requirements, and Brantley says solar companies are paying as much as $800 an acre in his area of the wheat belt for leases that last for decades. That’s $512,000 a year for a section of land—640 acres—an attractive lifeline for farmers increasingly strapped by rising input prices and unfavorable weather.

There is also a precedent. Wind came in about 15 years ago and turbines proliferated in the area, overall a net positive, Brantley says. But unlike wind, which is less lucrative and can coexist with crops, solar is pretty zero sum. “I know how fast it can happen. I’m afraid this thing might snowball. If solar catches on like wind did, all this cultivated land will go out of production,” says Brantley.

So far solar hasn’t started to really move into the Midwest, where the soil is considered superior, says University of Illinois ag professor Nick Paulson. It makes sense, he says, for solar companies to be more aggressive in a place like Texas given the relative quality of the farmland and more pervasive droughts. Still, Texas and Oklahoma represent about a quarter of planted acres of wheat in the U.S.

One part of the story is that investors have sought farmland as an inflation hedge. Bill Gates, the largest private owner of U.S. farmland, said on social-media platform Reddit earlier this year that his investment group is buying the land.

A May report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago said agricultural land values in the region surged 23% in the first quarter from a year earlier as investors bought a rising share of some of the country’s best farmland. Strategic Solar Group, which brokers land, says the high end of the average solar-farm lease is $2,000 an acre.

Another part of the story involves the government’s green agenda. While President Biden’s climate legislation suffered a new setback when Sen. Joe Manchin this month pulled his support, some lawmakers and analysts predict Biden will issue executive actions.

To achieve Biden’s goal for 100% clean electricity in the U.S. by 2035, the Energy Department says solar deployment will need to quadruple. Land.com, a marketplace for rural real estate, says generating electricity solely from solar farms would take 13 million acres—or double that to account for energy storage, electric vehicle charging stations, and the necessary increase in electrical infrastructure.

Apart from business incentives, government subsidies and tax credits also help explain why solar companies are aggressively seeking land.

Biden has pushed solar further into the mainstream than ever before, says Texas A&M University law and engineering professor Felix Mormann. There is lots of merit to seeking reduced emissions, cleaner air, and cheaper energy. But, Mormann asks, who ultimately pays for public spending on this scale and who will reap the economic benefits? The flip side of that question: At whose expense will those economic benefits be reaped?

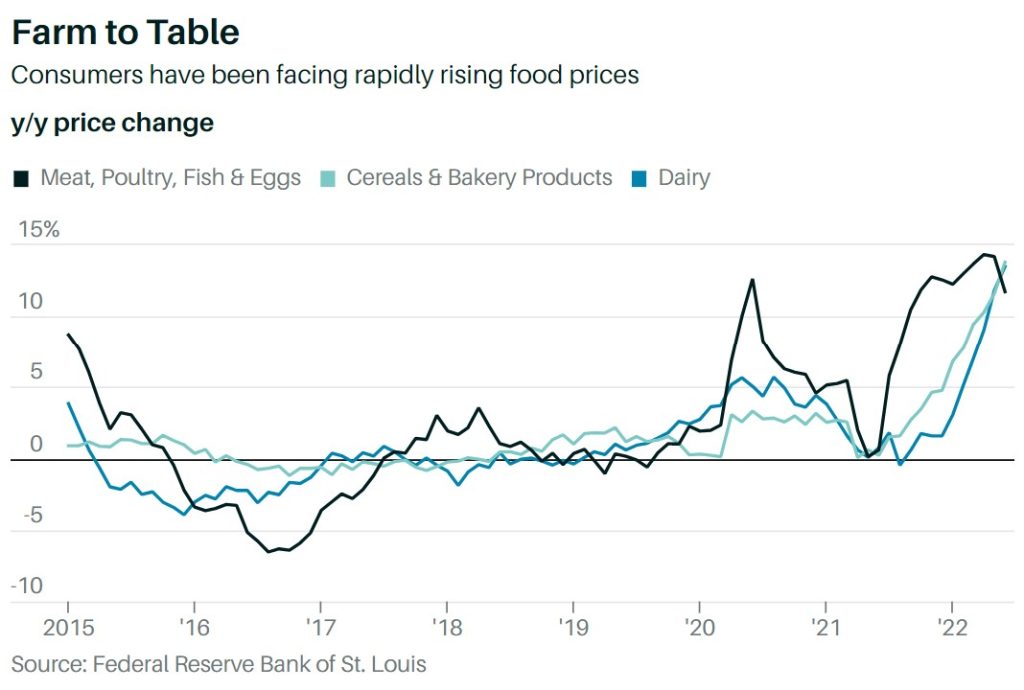

Already, Americans have seen double-digit price increases in food categories this year. In the latest consumer price index report, meats, poultry, fish, and eggs leapt 12% from a year earlier as bread rose 11% and milk increased 16%. That’s occurring as the U.S. Census Bureau has found about a 10th of Americans don’t have enough to eat.

The new deal between Russia and Ukraine to resume Ukrainian grain exports via the Black Sea should cool some commodity prices. But Paulson at the University of Illinois says falling food-commodity prices may not easily translate to less expensive food, in part because still-high oil makes up such a big portion of U.S. food costs.

Given the short supply of domestic oil, together with the impact of severe droughts and the war in Ukraine, the timing of solar’s encroachment on U.S. farmland may be cause for concern. [Barron]