The real Covid scandal is emerging right in front of the inquiry’s nose, writes Fraser Nelson in the Telegraph: Britain could have escaped the horrors of lockdown, but nobody pulled apart the doom models driving it. Here’s an excerpt.

Let’s go back to when much of the world had copied the Wuhan lockdown, with two major exceptions: Britain and Sweden. In both countries, public health officials were reluctant to implement a lockdown theory that had no basis in science. Ditto the case for mandatory masks.

The public had responded: mobile-phone data showed millions were already staying home. Could you really put an entire nation under house arrest, then mandate masks, if you had no evidence that either policy would work?

Sweden held firm, but Britain buckled. It was all decided in 10 fateful days where, thanks to inquiries in both countries, we know a lot more about what happened.

The written evidence submitted by Dominic Cummings is one of the richest, most considered, and illuminating documents in the whole Covid mystery. He was, in effect, the Head of Staff to a Prime Minister he viewed with despair, even contempt.

He has since admitted that he was discussing the possibility of deposing his boss within “days” of his 2019 general election victory. So he was prone to taking matters into his own hands, trying to circumvent what he regarded as a dysfunctional system and an incompetent PM.

His frustration, at first, was directed at the public-health officials who resisted lockdown. SAGE advisers were, at the time, unanimously against it. Even Professor Neil Ferguson fretted that lockdown might be “worse than the disease.” Was this the cool, firm voice of science – or the blinkered inertia of sleepy Whitehall?

Cummings suspected the latter and commissioned his own analysis from outsiders, whose models painted a far more alarming picture. He knew these voices would be dismissed as “tech bros.” But, he says, “I was inclined to take the ‘tech bros’ and some scientists dissenting from the public-health consensus more seriously.”

There was no SAGE modelling until quite late on but, soon, models and disaster-graphs were everywhere. Cummings’s evidence includes photos taken in No. 10 of hand-drawn charts with annotations like “100,000+ people dying in corridors.” He says he told Boris Johnson that failure to lock down would end in a “zombie apocalypse movie with unburied bodies.” The PM asked him, if this was all true, “why aren’t Hancock, Whitty, Vallance telling me this?”

It’s a very good question. Cummings told him the health team “haven’t listened and absorbed what the models really mean.” Soon, Neil Ferguson’s doom models were published – and making headway across the world. Britain’s scientists fell in behind the modellers.

It was a different story in Sweden where Johan Giesecke, a former state epidemiologist, had returned to the Public Health Agency and was reading Ferguson’s models in disbelief. Remember mad cow disease, when four million English livestock had been slaughtered to prevent the disease spreading?

“They thought 50,000 people would die,” he told his staff. “How many did? 177.” He recalled Ferguson saying 200 million might die from bird flu when just 455 did. Modellers, he argued, had been calamitously wrong in the past. Should society really be closed now on their say so?

On March 18th, Cummings had asked Demis Hassabis, an AI guru, to attend Sage. His verdict? “Shut everything down ASAP.” On the same day, Giesecke’s team in Stockholm was pulling apart Ferguson’s models, finding flaw after flaw. When some Swedish academics started to call for lockdown based on Ferguson’s work, Giesecke agreed to go on Swedish television to debate them. As did Anders Tegnell, his protégé. They gave interviews non-stop, in the street and on train platforms, making the case for staying open. They showed it was possible to win the argument.

Nelson points out that while one internal UK report said Covid patients would need up to 600,000 hospital beds, the actual number peaked at 34,000. Johnson was told that 90,000 ventilators were needed, but the actual peak was 3,700 – while all the extra ventilators ordered cost an extraordinary £569 million and ended up in an MoD warehouse gathering dust.

Noting, correctly, that new Covid cases were falling before the first lockdown, Nelson insists that the reason lockdown was not needed was because the voluntary behaviour change was enough to “force” the virus “into reverse.” This, too, is wrong, and also dangerous (though not so dangerous as lockdown) as it implies that even if lockdown is not required, people still need (and need to be encouraged) to cower in their homes when a virus is spreading. But to what end, since the virus is not going to go away and everyone will be exposed sooner or later?

The only realistic answer is some kind of healthcare rationing – stay home to protect the NHS and all that. But as Nelson notes, healthcare systems were nowhere near overload, and besides one of the main harms of lockdown – “eight million NHS appointments that never took place,” as Nelson puts it – is people staying away from getting the healthcare they need, so expecting them to do that voluntarily (and encouraging them to do so) hardly helps matters. Lockdown is bad because it keeps people away from healthcare, but we don’t need lockdown because people voluntarily stay away from healthcare is hardly a sound argument.

But the fundamental error in the ‘voluntary behaviour change was necessary’ position is that it fails to recognise that Covid waves, just like waves of other similar viruses, fall by themselves without any behaviour change. You need only look at charts showing winter flu waves and successive Covid waves to see that they all have the same shape – straight up and straight down. It’s the characteristic shape of a respiratory virus outbreak and there is no sign of it being affected by shifts in behaviour to any noticeable degree.

Thus, there is no reason to think that behaviour change – everyone staying home – was necessary to bring the first wave down any more than it was for any later wave or the flu every winter. The cause of the drop is likely in all cases to be much more due to the susceptibility of the population to the circulating strain (typically no more than 10-20 percent of the country are infected in any given virus wave) than any hiding away behind closed doors.

This point aside, Nelson is being a hero in making a big thing out of the failures of lockdown and the inadequacies of the Covid Inquiry to address the evidence properly – even making Carl Heneghan’s overlooked inquiry report in the cover piece for this week’s Spectator. Both Heneghan’s piece and Nelson’s Telegraph write-up are worth reading in full.

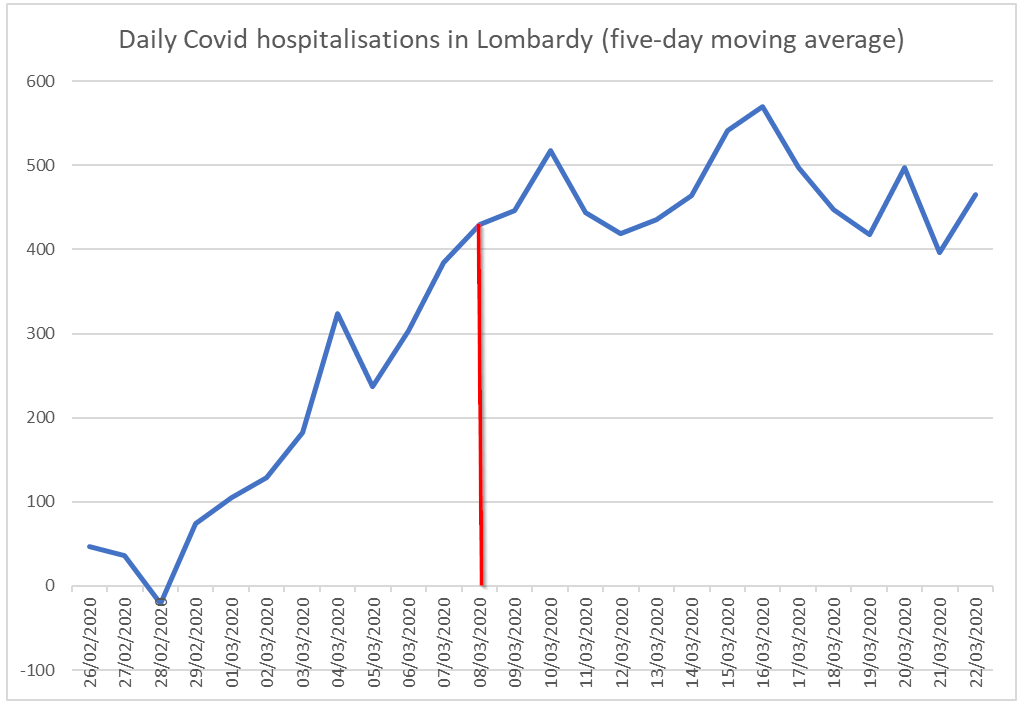

Stop Press: Heneghan and Tom Jefferson provide data from Lombardy which show behaviour change was not needed to bring down the first wave. Italy was locked down from March 8th (starting with the North), a date which coincided with when new daily Covid hospitalisations plateaued, as the following chart shows. Since new infections precede hospitalisations by at least a week, this indicates that the epidemic had stopped its explosive growth well before the lockdown.

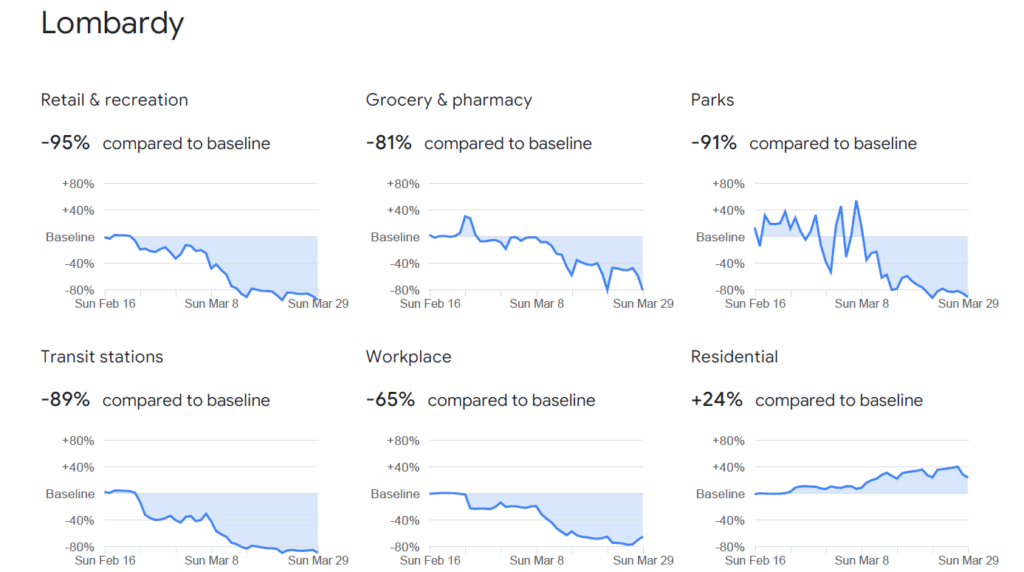

Google mobility data from Lombardy also show that there was no change in behaviour during the pre-lockdown period. While there was a drop in movement following the initial quarantine zone being imposed around a few towns on February 21st, there was no subsequent change that could explain why the outbreak slowed down in the week coming up to lockdown.

Source: The Real Scandal: Covid Inquiry’s Failure ⋆ Brownstone Institute