In last week, my substack was about the push for us to eat bugs and insects. The primary advantage claimed for eating insects is they have a high protein content. Fat, the second highest component of insects, provides healthier fats than fats in animal protein. Most insect analyses find they have a lot of minerals [manganese, copper, selenium, zinc, iron, calcium, riboflavin, biotin, folic acid, and pantothenic acid].

Food safety is a significant concern and is well documented in this article from March 2020. As I wrote previously, there is very little oversight of the processing regulations within this relatively new industry. There are also serious concerns about the health of farm raised insects and risk to humans of cross-contamination from what the bugs eat.

The published literature is limited regarding the shelf-life of commercialized insect products, whole or processed. When harvested in the wild, insects are eaten seasonally and immediately. Little is known about the stability of the nutritional profile. Does the protein degrade? Are the minerals stripped away during processing? No one really knows.

We also know very little about the digestibility and bioavailability (absorption) of insect nutrients. Even though laboratory assessments identify many nutrients (listed above), there are only scanty facts published about how much is actually absorbed. Insects can be processed by roasting, steaming, frying, boiling, or by being crushed into a powder (flour). Processing methods are rarely controlled, and it is unknown if a particular method adversely affects a bug’s digestibility and/or bioavailability.

According to several papers, it should not be assumed that the nutrient profiles on from a laboratory analysis translates to bioavailability when consumed by humans or animals.

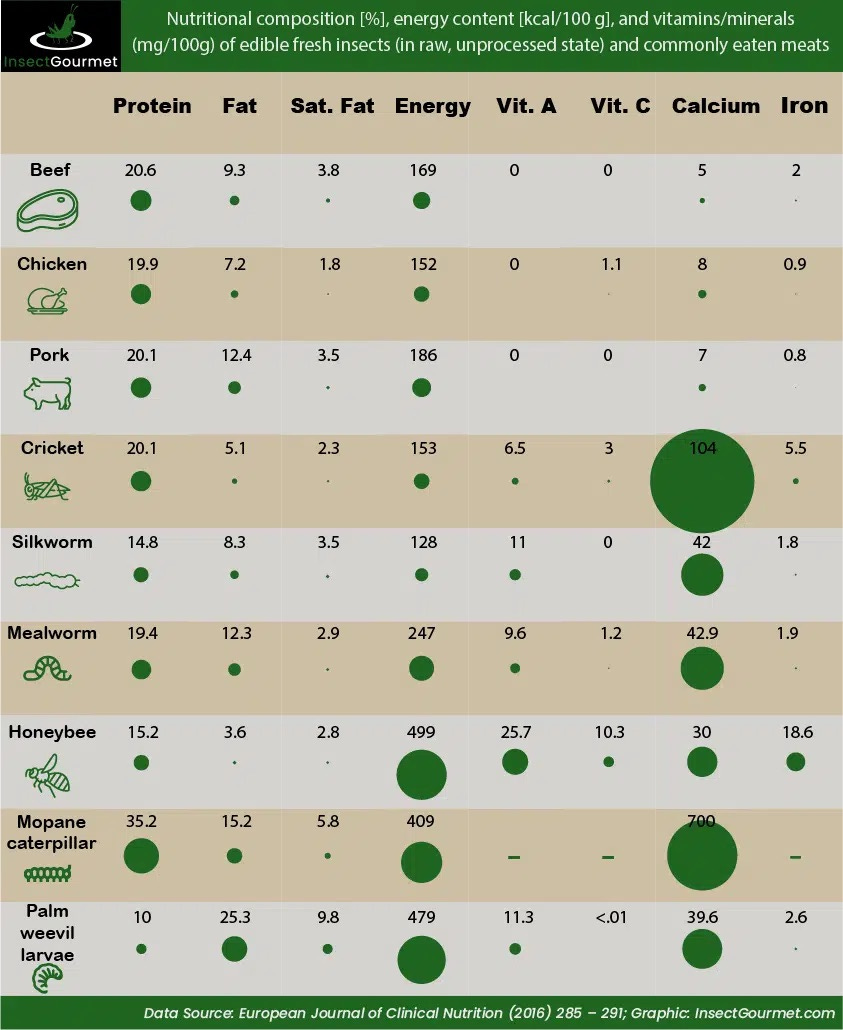

Nutritional comparison between bugs and beef have been made. This graphic outlines the differences and suggests why “sustainability”advocates are pushing the bugs. Source.

I received many good comments on Part 1, including a few questions about the potential hazards of ingesting chitin and chitosan found in the exoskeletons (shells) of the bugs. I dug in, but found limited information about its adverse effects except this:

The chitin in their hard shells (exoskeleton) has been linked to improved gastrointestinal health as a potential prebiotic. Chitin can also inhibit human gut microorganisms such as pathogenic E.coli and cholera. Its downside is that chitin can be highly allergic for some individuals. Chitin is responsible for the allergies in shellfish and therefore, if a person has a shellfish allergy, they should avoid insects and insect flour.

I spent many hours researching “chitin use” and found it is a MASSIVE topic. Both chitan, which can easily converted into chitosan, are used in almost every industry. After reading this article, I tossed in the towel about trying to find an association between eating insect chitin and side effects. It’s not very digestible and falls into the category of ‘insoluble fiber’ with the bug meal.

After sifting through dozens and dozens of articles, looking for articles on the “downside” of eating bugs (which I found very few), I did compile some additional information about eating insects that I found interesting and turned into this week’s Eye on the Evidence substack.

- Insects are touted as a major new source of protein, but scaling up to construct massive cricket farms could bring a new, massive problem — what to do with all their “frass.” Frass is a nice word for cricket poop. It is harvested, processed, and used for fertilizer on plants consumed by humans. It’s readily available; in fact, you can even buy it on Amazon.

- There are approximately 29 different commercially prepared products made from cricket powder. This is a site where you can buy cricket flour. Scroll down and look at the spreadsheet. All flours are not created equal! Let the buyer beware.

- It takes roughly 4,000 to 5,000 crickets to make 1 pound (0.45 kg) of cricket flour. That’s a lot of crickets.

- Pure cricket powder is quite expensive. Expect to pay between $13 to $16 per 100 grams, which is about $67.50 per pound (450 gm is approx. equal to 1 pound). In contrast, protein powders made from whey cost around $13.50 per pound (0.45kg). And one pound of plain ol’ all-purpose white flour costs about $0.52 per pound. Even through insect farms are touted to be less “resource intensive” and are promoted to create “sustainable farming opportunities” this isn’t translating to a cheaper baking products. Not even close.

- Cricket flour producers each use their own proprietary cricket feeds and processes – freezing, drying processes, grinding. In general, cricket flour production follows the same steps: crickets are dried and then ground by two different grinding or milling machines.

- The first machine is set to a coarse grind. Once the crickets have passed through this machine, the coarse cricket flour is sifted to remove the residual heavy bug parts such as legs, wings, etc.

- Next, the coarse flour is passed through a second milling machine, which is set to a fine grain size. The result is a fine, smooth cricket flour used for baking, etc.

- Most insect species are NOT edible. Of the 2,100 insects that are edible, the most common are crickets, honeybees and mealworms. Globally, beetles, caterpillars, wasps and ants are also commonly consumed.

- The global market for edible insect products is expected to grow more than 26% per year by 2027, reaching annual sales of around $4.6 billion. Insects are currently used in many foods, including protein bars, breads, chips, pasta, noodles, soft drinks, milks, candies, ice creams, buggers, oils, spices and seasonings. Here is a source for insect snacks and candies.

- Lac bugs, raised commercially in India and Thailand, are sought after for their waxy coatings. Workers scrape Lac bug secretions from host plants. The waxy particles are are turned into flakes called sticklac or gum lac. If a package ingredient lists GLAZE or RESIN, it is a clue that Lac bug goo is in or on the food. Gum lac is also used in cosmetics and on medications (to make them easier to swallow.)

- The following information was found on www.InsectGourmet.com, but apparently it was extracted from a book written in 1992, “Invisible Bugs and Other Creepy Creatures That Live With You”, by Susan Lang. It is a list giving an idea of how these bugs taste. I’m reposting here to save you some time and perhaps satiate your curiosity about how the crunchy critters taste:

- Raw termites taste like pineapple and cooked termites have a delicate, vegetable flavor.

- Grubs (which are larvae) of palm weevils taste like beef bone marrow.

- Fried agave worms (canned in Mexico) taste like sunflower seeds.

- Diving beetles (available in Chinatown in San Francisco) taste like clams.

- Fried grasshoppers taste like sardines.

- French-fried ants (imported from Colombia) taste like beef jerky.

- A praying mantis, fried over an open fire, tastes like shrimp and raw mushrooms.

- Fried wax moth larvae taste like corn puffs or potato chips.

- Fried spiders taste like nuts.

- Fried baby bees taste like smoked fish or oysters.

**Source: Eating Bugs and Insects – Part 2 – by Dr. Sherri Tenpenny